Pathways to Reparation for Sudan's Victims

- Mariana Goetz

- Dec 8, 2025

- 2 min read

On 3 December 2025, Sudanese partners teamed up with Rights for Peace and REDRESS to hold a side event at the ICC Assembly of States Parties in The Hague on reparation for Sudan's victims.

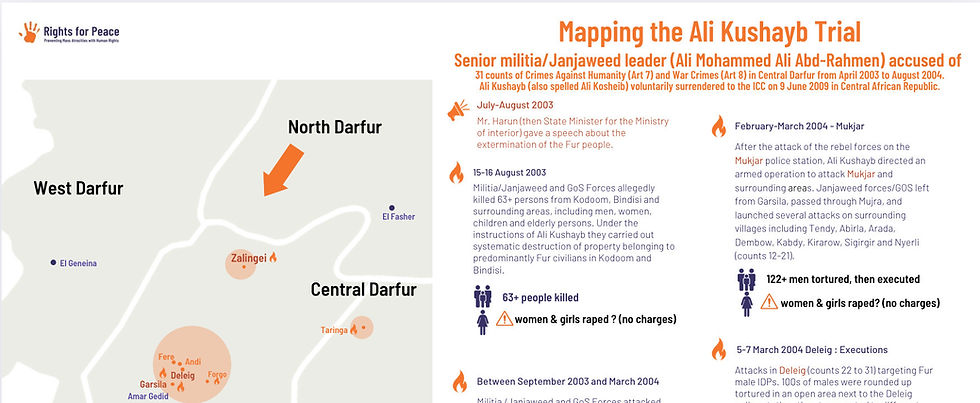

The discussion was framed within the context of the first ICC conviction in the Darfur Situation on 6 October 2025, in the case of Ali Muhammad Ali Abd-Al-Rahman (“Ali Kushayb”) , which paves the way for the Court’s first Reparations Order for Sudanese victims. The discussion also drew out the significant challenges for implementing reparation for the case's victims estimated at potentially 40,000 and the remaining impunity gap that leaves countless others with limited prospects of redress at this point.

While the Ali Kusheyb conviction represents a landmark for accountability in Sudan, it also underscores the immense challenges of making reparations a reality. Delivering reparations amidst an ongoing conflict presents immediate obstacles: most of the victims in the Al-Rahman case remain displaced within Darfur, confronted with renewed atrocities and persecution along ethnic lines. Moreover, the crimes addressed in this case capture only a fraction of the atrocities committed during 2003–4, focusing on specific attacks in just four locations. Key individuals subject to ICC arrest warrants are still at large, leaving the vast majority of victims without access to justice.

At the national level, plans for broader reparation and transitional justice outlined in the 2020 Juba Peace Agreement have been largely derailed. As the war continues to generate new patterns of victimisation and deepen existing harm, the near absence of meaningful discussion about reparations - both for past atrocities and the ongoing violence - represents an uncomfortable double standard compared to other conflicts such as Ukraine.

The panelists representing Darfur Women Action Group, International Community Care, SIHA and the Sudan Rights Monitor raised the need for urgent measures as well as discussion of impunity at national level and the need for national level reparation measures within the context of future transitional justice processes.

The need for interim administrative reparation, or assistance in the case of the ICC’s mandate, is urgent. Establishing mechanisms that can provide urgent psychosocial support and material assistance—while comprehensive reparations are being developed—is vital. Can efforts to document and verify harm through the UN fact-finding mission play a role in shaping interim measures? Could such urgent measures be delivered through an existing UN Trust Fund?

Comments